Beijing (AFP) – They said they had smashed them. But fraud factories in Myanmar blamed for scamming Chinese and American victims out of billions of dollars are still in business and bigger than ever, an AFP investigation can reveal. Satellite images and AFP drone footage show frenetic building work in the heavily guarded compounds around Myawaddy on the Thailand-Myanmar border, which appear to be using Elon Musk’s Starlink satellite internet service on a huge scale.

Experts say most of the centers, notorious for their romance scams and “pig butchering” investment cons, are run by Chinese-led crime syndicates working with Myanmar militias in the lawless badlands of the Golden Triangle. China, Thailand, and Myanmar pressured the militias into vowing to “eradicate” the compounds in February, releasing around 7,000 people from a brutal call center-like system that runs on greed, human trafficking, and violence. Freed workers from Asia, Africa, and elsewhere showed AFP journalists the scars and bruises of beatings they said were inflicted by their bosses. They said they had been forced to work around the clock, trawling for victims for a plethora of phone and internet scams.

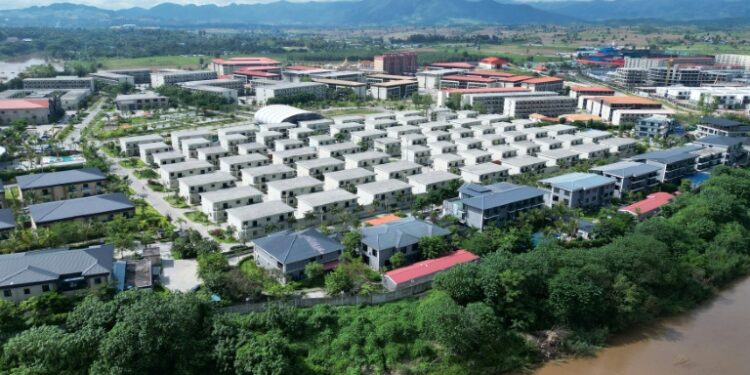

Sun, a Chinese national who was sold between several compounds, was able to give AFP a rare insider’s account after being freed with Beijing’s help. But a senior Thai police official said after the crackdown began that up to 100,000 people may still toil in the compounds — often mini cities surrounded by barbed wire fences and armed guards — that have sprung up on the border with Myanmar since the Covid pandemic. Satellite images show rapid construction work resuming at several compounds only weeks after the crackdown. Flocks of Starlink satellite dishes soon began to cover many scam center roofs after Thailand cut their internet and power connections. Nearly 80 Starlink dishes are visible on one roof alone in AFP photographs of one of the biggest compounds, KK Park.

Starlink — which is not licensed in Myanmar — did not have enough traffic to make it onto the list of the country’s internet providers before February. It is now consistently the biggest, topping the ranking every day from July 3 until October 1, according to data from the Asian regional internet registry, APNIC. It first appeared at number 56 in late April. California prosecutors officially warned Starlink in July 2024 that its satellite system was being used by the fraudsters, but received no response. Worried Thai and US politicians have also conveyed their alarm to Musk, with Senator Maggie Hassan calling on him to act. Now the powerful US Congress Joint Economic Committee, on which she is a leading member, has told AFP it has begun an investigation into Starlink’s involvement with the centers. SpaceX, which owns Starlink, did not reply to AFP requests for comment.

Erin West, a longtime US cybercrime prosecutor who resigned last year to campaign full-time for action, said, “it is abhorrent that an American company is enabling this to happen.” Americans are among the top targets of the Southeast Asian scam syndicates, the US Treasury Department said, losing an estimated $10 billion last year, up 66 percent in 12 months.

The building boom since the crackdown is “breathtaking,” West said. Satellite images show what appear to be office and dormitory blocks shooting up in many of the estimated 27 scam centers in the Myawaddy cluster, strung out along a winding stretch of the Moei River, which forms the frontier with Thailand. A whole new section of KK Park has sprung up in seven months. The security checkpoint at its main entrance has also been hugely expanded, with a new access road and roundabout added. At least five new ferry crossings across the Moei have also appeared to supply the centers from the Thai side, satellite images show. They include one serving Shwe Kokko, which the US Treasury calls a “notorious hub for virtual currency investment scams” under the protection of the Karen National Army, a militia affiliated with Myanmar’s junta.

Last month, the US sanctioned nine people and companies connected to Shwe Kokko and the Chinese criminal kingpin She Zhijiang, founder of the multistory Yatai New City center. Construction work in Shwe Kokko has also continued apace. The borderlands where Myanmar, Thailand, China, and Laos meet — known as the Golden Triangle — has long been a hotbed of opium and amphetamine production, drug trafficking, smuggling, illegal gambling, and money laundering. Corruption and the power vacuum created by civil war in Myanmar have allowed organized crime groups to dramatically expand their scam operations. Southeast Asian scam operations conned people in the wider region out of $37 billion in 2023, according to a report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, which said the gangs ruled the centers with an iron fist.

Many workers extracted from the compounds in February said they were trafficked through Thailand and beaten and tortured into working as scammers. Others said they were lured by false promises of well-paid jobs. However, experts and NGOs said some also go willingly. Beijing pushed authorities in Myanmar and Thailand to crack down in February after Chinese actor Wang Xing said he was lured to Thailand for a fake casting and trafficked into a scam center in Myanmar. Last month, China sentenced to death 11 members of a scam syndicate that operated just over the border with Myanmar, with five more given suspended death penalties.

AFP has been able to build up a picture of the murky world of the centers and the overlapping militias who guard them after months of investigation. It is a ruthless industry full of slippery characters willing to sell people into the compounds or broker their release — for the right price.

Sun — a pseudonym AFP is using to protect his identity — is one of thousands of Chinese people swallowed up by the scam factories. The soft-spoken young villager from the mountains of southwestern Yunnan province told AFP how he and other workers were repeatedly beaten with electric rods and whips if they slacked or did not follow orders. “Almost everyone inside had been beaten at some point…either for refusing to work or trying to get out,” he said. But with high fences, watchtowers, and armed guards, “there was no way to leave,” until he was released with 5,400 other Chinese nationals since the February crackdown.

Sun’s testimony is a rare insight into the internal workings of the centers, as he was sold on between several when bosses realized that a slight physical disability limited his usefulness. AFP journalists managed to talk to him as he was being released and later on the phone, as well as back in his poor, isolated village. Sun said his trouble began in June 2024 when he left his home some 100 kilometers (60 miles) across the mountains from Myanmar. With one child already and another on the way, the 25-year-old wanted to provide for his family and had heard there was money to be made selling Chinese goods online through Thailand. “I heard it was very profitable,” he told AFP.

The trip turned into a nightmare in the Thai border city of Mae Sot, where Sun said he was abducted and taken over the slow river that divides it from Myanmar’s Myawaddy and its infamous scam centers. He said he was “terrified. I kept begging them on my knees to let me go.” Once in Myawaddy, he said, his plight quickly worsened. Sun said he was brought to a militia camp where he was sold for 650,000 Thai baht ($20,000) to a scam center — the first of several such transactions. There, he was ordered to do online exercises to speed up his typing. Sun, however, had a problem: a deformed finger that slowed him down and drew the ire of his overseers. The disability, verified by AFP, meant he was repeatedly sold on to other compounds and given menial tasks.

But in the last facility — bristling with high fences and gun-toting guards — he got a taste of the real work, sending unsolicited messages to scam targets in the United States. Once the victims were on the hook, he said, he passed the target on to a more specialized scammer who would continue the conversation. Experts confirmed that many Chinese-run compounds split the workforce according to their scamming ability. The centers also provide workers with detailed scripts on how to bait their targets. One 25-page text seen by AFP suggested workers adopt the persona of “Abby,” a lovesick 35-year-old Japanese woman. It advised them to build a romantic rapport with the target. “I feel we are so destined,” the document suggests Abby could say.

Much about the industry is opaque, mirroring China and Thailand’s complex relations with Myanmar’s military regime and various rebel and junta-allied groups, many of whom profit from the illegal mining, logging, and drug manufacturing going on amid the war there. Scam center staff run the “whole gamut,” from expendable grunts held in slave-like conditions to skilled programmers working for high salaries, said veteran Myanmar expert David Scott Mathieson, a former Human Rights Watch monitor. Chinese authorities are treating those like Sun who were brought out in February as “suspects” who may have ventured knowingly into war-torn Myanmar. AFP verified key pillars of his story, consulting several experts on the centers. But other portions were harder to confirm — with Thai authorities not providing information, and Chinese officials tailing our reporters and impeding efforts to talk further with him.

AFP journalists were followed by multiple unmarked cars while traveling to see Sun in his mountain village, three hours from the nearest city, Lincang. Minutes after AFP met with him, a flurry of officials arrived to “check up” on his welfare. When Sun returned after half an hour, he declined to speak further.

In the weeks before his extraction, Sun wondered if he would ever be able to escape the drudgery, threats, and violence of the scam centers. “I thought about the possibility (of dying)…almost every day,” he told AFP. AFP obtained a copy

© 2024 AFP